EPISODE TWO: WHEN THE PROMISES BROKE

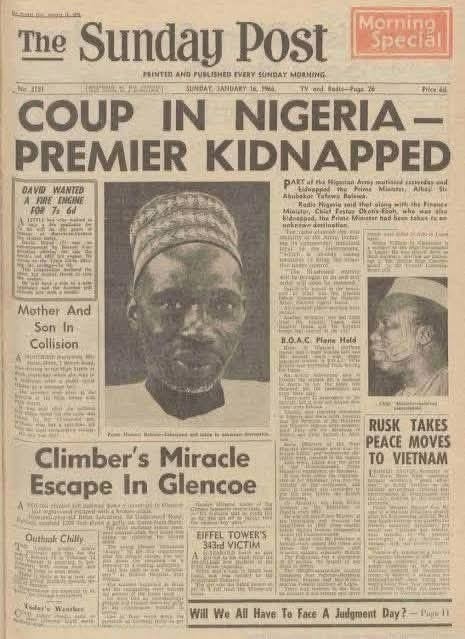

On the morning of January 15, 1966, Nigerians woke up to a country they no longer recognised. Before dawn, soldiers had moved through Kaduna, Lagos, Ibadan, and Enugu with stealth and precision. By the end of the day, quite a number of politicians were either missing or killed, senior officers in the military were ambushed, and government authority had been effectively shattered. For many citizens, the first confirmation came not from officials in Lagos, but from Radio Kaduna. The voice that came through did not sound like a reassurance but a verdict.

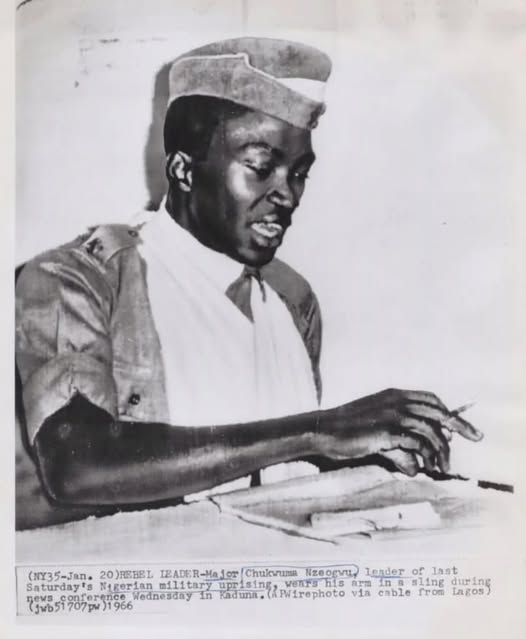

Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu’s broadcast was sharp, moralistic, and unlike anything Nigerians had heard from their leaders. Gone were the polished lines of Independence Day speeches. He spoke of “political profiteers… swindlers… men who seek bribes and demand ten percent.” His speech was not simply a justification for the coup; it was a public indictment of the First Republic. And for many Nigerians, it captured something they already felt but had not articulated: the promises of independence had begun to collapse long before the soldiers arrived.

To understand why the 1966 coup resonated so widely, you have to look at the slow breakdown that preceded it.

The early optimism of independence did not survive the crises of the early 1960s. By 1962, politics had become a battlefield. The Action Group crisis in the Western Region (a dispute between Awolowo and his deputy, Akintola) grew into a full political fracture. What started as ideological disagreement escalated into violent street clashes, burnings, and targeted attacks. The period later known as Operation Wetie or “Wild Wild West” symbolised how far the democratic project had drifted. State institutions struggled to contain the violence. Public trust evaporated due to perceived biases and partisanship.

At the national level, tensions grew worse. The 1962 census collapsed into controversy. The 1963 recount did not settle the matter; it further deepened suspicion. The 1964 federal elections were discredited by boycotts and intimidation. And the 1965 Western Regional elections triggered violence so intense that many Nigerians openly questioned whether democracy had a future.

This was the environment in which political speeches began to lose their power. Leaders still invoked unity, brotherhood, and discipline, but the gap between rhetoric and reality widened daily. Citizens heard the speeches, but they no longer believed them.

Do you see a similarity today?

Why Nzeogwu’s Broadcast Hit the Way It Did

What made his message different was not the language itself but the way he used them. Themes like honesty and discipline had appeared in earlier speeches, but his rendition stood out. Where Azikiwe had used such words to appeal, Nzeogwu used them to condemn. He was not asking for national unity; he was asserting that the political class had betrayed it.

For many Nigerians, especially in regions where the crises had been most severe, the broadcast felt like a brutal but familiar truth. In the North, early reactions included cautious approval. In the West, exhausted by political violence, some citizens expressed relief that someone had taken control. In the East, responses were more restrained, coloured by concerns about who had been targeted in the coup.

But across regions, one sentiment was consistent: the politicians no longer controlled the national narrative. Someone else (uniformed, armed, confident) had stepped in to define the country’s direction.

In actual sense, the coup did not erase political rhetoric, it simply changed its tone. In the days following the intervention, military leaders adopted the same themes that civilians had used the word ‘unity, discipline, national survival’ but the meaning shifted. These were no longer appeals rooted in persuasion but instructions backed by authority. The vocabulary remained familiar, but the centre of power had moved from the parliament to the Supreme Military Council.

This transformation matters because it marks the first major rupture in Nigeria’s rhetorical tradition. From 1960 to 1966, civilian leaders used language to build consensus, manage crises, and hold together a fragile federation. After the coup, the military used similar words, but as instruments of control.

This episode reveals the point at which the promises of early independence finally broke under the weight of political crisis. By January 1966, the gap between what leaders said and what citizens experienced had become impossible to bridge. The rhetoric of unity and progress no longer reassured anyone. That vacuum created the space for Nzeogwu’s broadcast, and for the new political language that would dominate the years to come.

In Episode Three, we will follow this shift into the era of counter-coups and the Civil War: a period when rhetoric about unity, survival, and sacrifice took on deeper, more urgent meanings and when political language began to reflect not just hope, but existential struggle.

Thanks for reading. Let us know what you think in the comments.

Leave a comment