EPISODE ONE: The First Promises

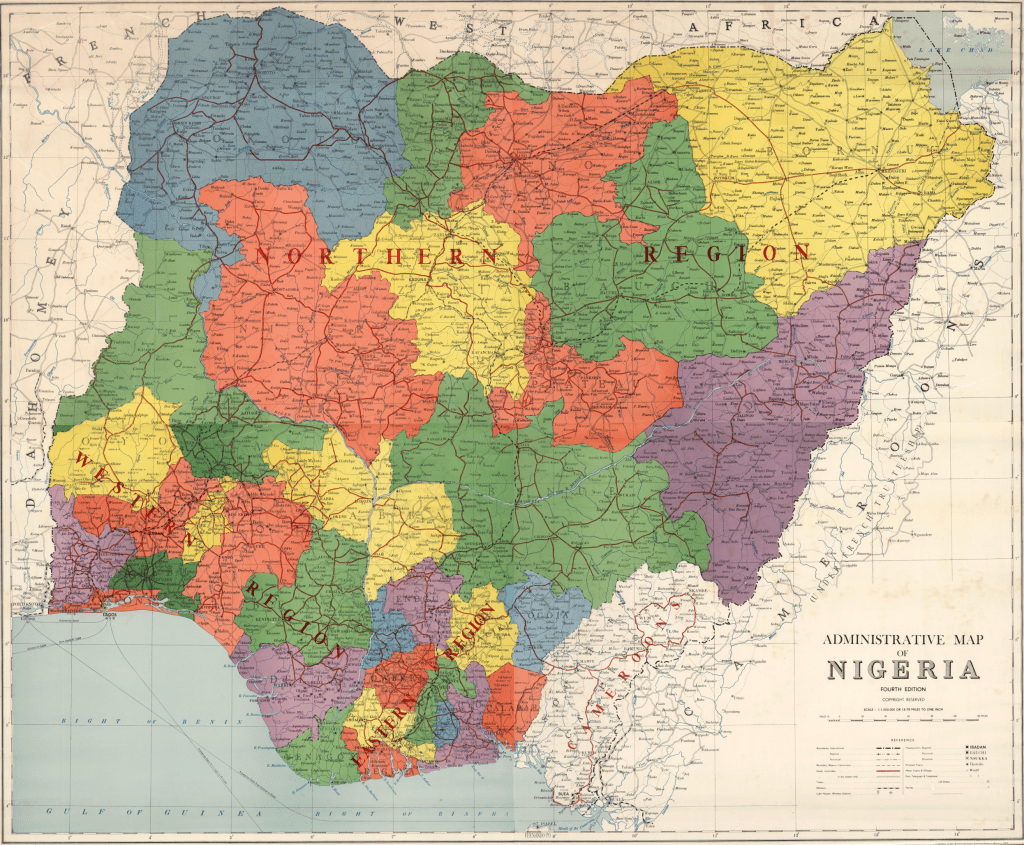

In 1960, Nigeria became independent. The euphoria was real, but fragile. Three regions, each with distinct histories and political ambitions, were suddenly asked to govern themselves under a federal system. Unity was therefore not guaranteed; democracy was only an experiment. In this context, every speech from the national stage carried a weight far greater than ceremony. These speeches were instruments of reassurance. They served as appeals to cohesion and subtle warnings.

By 1962, the first cracks appeared. The Action Group, dominant in the Western Region, fractured. Awolowo and Akintola clashed over leadership, party structure, and policy, turning the Western Region legislature into a battleground. The crisis quickly became national, raising doubts about the viability of democracy itself. Politicians across the country watched as trust between regions eroded, and ordinary citizens began questioning the promises of independence.

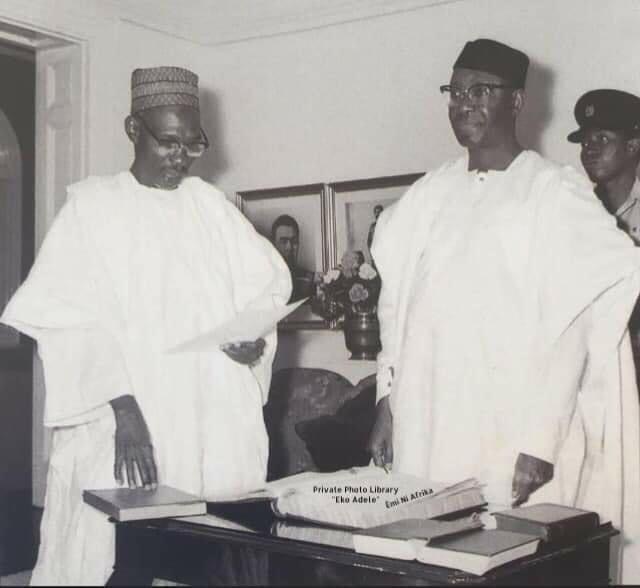

It was against this backdrop that Nnamdi Azikiwe addressed the nation:

“Let us renew our faith in liberal democracy and strengthen our belief in the greatness of our country.” (1962 Independence Day Speech)

Contrary to popular beliefs, these words were not just patriotic exhortation on a national day, but a deliberate attempt to restore confidence in a system already under stress. Azikiwe was not only speaking to the citizens, he seemed to also be addressing the emerging power of the military, a silent observer of civilian failures.

Two years later, the tensions over identity and representation had intensified. The 1963 census had sparked allegations of manipulation, feeding regional suspicion and inflaming ethnic consciousness. Political rhetoric increasingly addressed not policy but cohesion. In his 1964 address, Azikiwe invoked a line from the national anthem:

“Though tribe and tongue may differ, in brotherhood we stand. Let us give meaning to these words by living and working together.”

These words were not symbolic; they were a response to a real threat – a nation on the verge of fragmenting along ethnic lines. Interestingly, decades later, the administration of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu reintroduced this old anthem officially. Senate President Godswill Akpabio argued at the time:

“If we had kept to that anthem, we probably would not have banditry today in Nigeria because if you take your neighbour as your brother, you will not want to kill him.”

But that is a digression for another day. Returning to the early 1960s: the federal elections of 1964 and the ensuing violence in the Western Region, later dubbed the “Wild Wild West” or “Wet tie” crisis, intensified the stakes. Political rhetoric became both shield and strategy. Leaders promised peace, discipline, and unity while the country witnessed arson, intimidation, and targeted attacks. The language of promise was a mechanism of control: to assure, to persuade, and to postpone the inevitable confrontation.

By 1965, the military was observing these developments with increasing concern. Civilian authority appeared ineffective, and the prospect of intervention grew. The promises made by politicians, while aspirational, also underscored the fragility of the republic. Gowon’s 1966 Independence Day address illustrates the continuity of the message, even as the voice shifted from civilian to military:

“We must rediscover honesty and sincerity. Let us dedicate ourselves to discipline, loyalty and service.”

“Our nation must remain united. It is only in unity that our progress can be guaranteed.”

The words remained familiar, unity, progress, discipline, but their delivery signaled a change in authority. Whereas early promises sought to inspire, military rhetoric sought to command. Yet the underlying narrative of hope persisted, as though the nation’s imagination required a constant reminder that a better Nigeria was always within reach.

Looking back, the first promises of independent Nigeria reveal two enduring truths. The first is that rhetoric is inseparable from the context in which it is delivered. Every speech, every line of persuasion was a response to political crises, social anxieties, and regional tensions.

Second, the themes of unity, progress, and renewal established in the 1960s have endured. They continue to resonate because they address the same hopes, fears, and expectations of Nigerians today.

Episode One closes here, not with resolution but with foreshadowing. The promises of 1960–1966 laid the groundwork for the challenges that would erupt in 1966, as the nation confronted civil war, further coups and the first tests of the rhetoric’s durability. Understanding these first promises is essential to tracing how political language shapes not only expectations but the trajectory of the nation itself.

Leave a comment